Thomas Jordan (B.1892): Home and Family

Family is a central theme in Thomas Jordan’s memoirs, but in a less than traditional way. He does not so much focus on his own family, his wife and children, but specifically about his mother and father. Thomas was part of a mining family in the North-East of England in Usworth, County Durham. Living in a colliery, he was aware of his class from an early age yet it never appeared to hinder him throughout his life. Academic author Pierre Bourdieu has said that consciousness of class is first learned and felt in the immediate home and neighbourhood, so living in the colliery would have sheltered Thomas from outside influences, yet at the same time it would have confirmed his social standing. He explains how he enjoyed the escapes of the countryside to ‘compensate against any ugliness of the pit’ (Jordan, 2) however he was later able to make his escape, even if it was just for the inter-war years.

At a young age Thomas knew he wanted to follow his father into the Army, and he eventually did at the age of 20. He recalls in his memoirs the events leading up to, and the conversation he had with his mother when he decided to leave for the army. He remembers how his mother ‘pleaded with me not to go. My earnings were helping her to run the home’ (Jordan, 6). In the early 20th century, the men of a family were expected to give their time and labour to earn for the family, while on the contrary, girls weren’t expected to work but to marry at what would be considered a young age in today’s society. Thomas remembers;

‘they all married- well early- in their twenties they were married, perhaps when they were twenty-one – that was the common age in those days, of girls getting married- so somebody else would keep them. You see.’ (Jordan, 11)

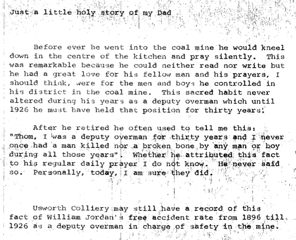

Thomas does not express affection towards his father, but rather he tells stories of how he provided, and how he was a protector of the family, and of the colliery in general. Julie-Marie Strange has explained this concept by highlighting that autobiographers ‘signal their affectionate relationship with their father by talking about the things he did for them & the things he made them’ (Strange). This being said, he does express ‘I thought he was marvellous’ (Jordan, 10) regardless of the fact the he was uneducated and had worked down the mines until he was seventy-two, not exactly what Thomas had in mind for his own future. Additionally, Thomas includes a section at the end of his memoirs where he introduces a ‘Just a little holy story of my Dad’ section. He shares the fact that his father had a ‘free accident rate from 1896 till 1926 as a Deputy Overman in charge of safety in the mine’ (Jordan, 19) which highlights the importance of his father to the community and not just to his family.

Although there is a page missing from his memoirs, in which he talks about his wife, I am aware that Thomas married a young lady from the local area when he was in his 20’s. His wife was a teacher and they went on to have children and remain in the North East. The interviewer asks Thomas ‘That was unusual wasn’t it? The miner marrying somebody that was a teacher?’ (Jordan, 9) and Thomas jokes that his young wife must ‘have had more romance in her than brains’ (Jordan, 9). He explains how his wife bettered his education by encouraging books to be kept in the house, he stated that ‘I didn’t know anything about education- but reading these books I began to get interested… the little distance I’ve gone, it was due to her’ (Jordan, 9). Yet Thomas also explains that his wife ‘was a girl who belonged to a mining family’ (Jordan, 9) which suggests that there was little chance to move beyond your social class in terms of marrying someone of a higher class, or indeed just of a different background.

Thomas talks about his mother being a ‘thrifty women’ and explains that their family ‘were assured of warm clothing in the winter made up from material bought at cost price from shop sales’ (Jordan, 1). This allows us insight into the family home in the early 20th century and we can see that working-class women were beginning to withdraw from industrial life and into the home, where they ‘tried to emulate the domestic lifestyles of the wealthy’ (Rosemary Collins, cited by Bourke, p. 62). Thomas said that the ‘family of six never knew the hardships which seemed to be common at that period’ (Jordan, 1) which supports this argument of appearing to live beyond your class.

Historian Valerie Hall has highlighted that the role of the woman in a mining family was ‘wholly domestic… [and] all-consuming’ (Hall, 50) which is supported by Thomas in his description of his mother. This being said, however, Thomas takes time to explain the dynamics of a mining town, in which he describes how his parents were well respected and greatly appreciated in the community due to the closeness of a mining town. His mother would be called upon to help deliver babies of the colliery, and his father was regularly asked to be an underbearer.

‘Oh she- she must have spent hours and hours with women having children… and he must have carried hundreds of bodies- helped to carry them to the graves.’ (Jordan, 12)

Although he does not go into great detail about his childhood, his home life or his family, he says enough to know that it was a happy environment for him to grow up in, only he knew that one day he would leave to see more and to feed his imagination. From living in the common dirt of the colliery, sharing a bedroom with his siblings whilst his parents slept in the kitchen, Thomas eventually made it to the clean barracks in Aldershot only to poetically return to start his own family in the familiar setting of the colliery.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Harvard University Press, 1984.

Bourke, Joanna. Working-Class Cultures in Britain, 1890-1960: Gender, Class and Ethnicity. London: Routledge, 1994 p. 62

Hall, Valerie G. Women at Work, 1860-1939: How Different Industries Shaped Women’s Experiences. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2013.

Strange, Julie-Marie. Fatherhood and the British Working Class, 1865-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014

Thomas, Jordan. Untitled. Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiography, University of Brunel Library, Special Collection, 1:405

Leave a Reply