John Gibson (1887-1980): Politics & Protest [Part One]

‘If there was a party on, I was in it’ (1).

Due to how important politics was for John Gibson, it is no surprise to find that the majority of his interview is dedicated to it. The transcript features many famous names, including leading figures of the labour movement, some of whom later went on to serve in Parliament. Part one of this Politics & Protest feature deals with John’s relationship with these key figures, as well as his involvement with various socialist organisations.

John was heavily involved in the workers’ movement throughout his life, with the transcript focusing particularly on the period during and after the First World War. He proudly states that ‘if there was a party on, I was in it’ (1), holding membership with the British Socialist Party and the Labour Party. As a ‘keen Labour Party member’ (6), John was ‘interested in a meeting of any kind’ (2), often attending political debates and never shying away from speaking his mind. This often made his relationship difficult with those in positions of authority, clashing with management in both the Labour Party and his trade union, the ASE. By his own admission John ‘canna [sic] keep quiet for long’, recalling how ‘I was one of these side-fellers that used to kick up a row’ (6). This combative, straight-talking approach earned him a reputation as a ‘wild character’ (2), both in Glasgow and the north of England.

This reputation followed him down to Letchworth, where he worked in a factory. Ever involved with trade unionism alongside his work, John reveals how his fellow union members ‘didn’t like me, because I was from Glasgow’ (6), a hotbed of radical politics at the time. However, ‘a year after they were all in my favour’, so much so that ‘they elected me on the Trades Council at the first Trade Union branch [meeting] I went to’ (6). The election came about after his predecessor on the council, a man by the name of Larry Freeman, had been expelled due to the fact that ‘he wasn’t representing anybody except himself’ (6). John therefore ‘suggested they should cut him out altogether and put my name down, and that’s just what they did. And of course it got all over town…they talked about this wild man from Glasgow’ (6).

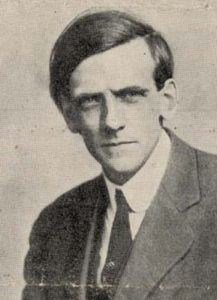

John seemed to make an instant impact wherever he went. Again in Letchworth, he was appointed shop steward after merely ‘“two days in this town…in a factory I know absolutely nothing about”’ (6). On another occasion, after bumping into ‘“an old friend”’ (6) in James Maxton, John was invited to attend an ILP (Independent Labour Party) meeting despite not being a member. When reminding the group of this, Maxton replied ‘“it doesn’t matter whether ye are or not, ye’re [sic] coming”, and I finished up in the committee of the ILP’ (5). Maxton was a well-known socialist figure who ‘was found guilty of sedition… [in] 1916 and imprisoned for twelve months’ (WCML). For John to have been elected onto the committee of the ILP after not even holding membership before the meeting demonstrates just how much he was valued by his colleagues in the movement.

The existence of the ILP predates the Labour Party, and it was in fact instrumental in the founding of the latter organisation. ‘In 1900 the ILP joined with the trade unions and other socialist groups in forming the Labour Representation Committee, which became the Labour Party in 1906’ (WCML). John’s recollection that ‘all the heads of the Labour Party were ILPers, and they were pretty well-to-do’ (6), highlights their influence in the party, as well as raising the question of how suitable these ‘well-to-do’ members were for carrying-out the task of representing the working class in their political struggles.

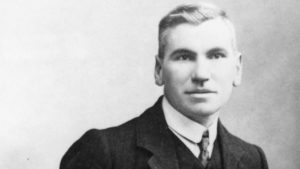

John discusses a great many fellow socialists involved in the labour movement during the early 20th century. During the Red Clydeside period of radical politics, there were many ‘“fighters up in Glasgow”’, and ‘I was amongst them’ (3). John reveals his ‘gang’ of close activist friends, including ‘George Hardy…the brother of Kier Hardy…[and] John Maclean’ (3), whom he clearly held in high regard. John is full of admiration for Maclean, describing him as ‘an educated man, [who]…would stop and speak anywhere, he didn’t need notes; he had a mind [and] he used to speak his mind’ (4). Maclean’s talent was such that he could address any audience and still communicate effectively. ‘He would lecture anywhere, in halls or on the streets or anywhere…he was outstanding’ (5).

Maclean was often arrested and imprisoned for his beliefs but never abandoned the cause, another thing John praises him for. ‘[Maclean] was arrested a number of times, because he wouldn’t give up; his wife left him, or he left his wife; his family broke up, because he wouldn’t give up the workers’ fight’ (6). John remembers a bit of friction existing between Maclean and William Gallacher, another key political figure who John values greatly, but expresses confusion as to the underlying reason. ‘I really don’t know why there was this animosity between Willie Gallagher [sic] and John Maclean, because Gallagher made me realise that I was alive. He used to speak all over the shop; on Glasgow Green thousands of people used to hear him’ (6). To John, both men were excellent orators and wonderful servants to the workers’ fight during this time.

However, John was not full of praise for everyone in the movement, even criticising men that went on to be quite powerful. ‘I always had close contact with two who later on became Lords, Manny Shinwell…he was always one of the fellers [sic] that I didn’t like…and Davie Kirkwood”’ (4). Although he does not detail his reasons for disliking Shinwell, it appears he viewed Kirkwood as somewhat of a sellout, who after gaining power then abandoned the fight that had gotten him elected in the first place. When discussing this with Kirkwood himself, ‘the excuse he gave…was that…you’ve got to do practically as Rome does. If you were amongst wealthy people, you’ve got to be as they are’ (4). He claims Kirkwood ‘always left it to other people to do…He says “WE’LL GIVE EM HELL”…[but] when he got to Parliament…he was like a little lamb at the end’ (5).

John’s brutal honesty, as shown here, was what served him so well in his political career, as well as making this transcript all the more fascinating. He was an active member of various socialist organisations and had no qualms about raising issues in meetings or criticising his colleagues. On the whole however, much of what John has to say about his fellow activists is positive and complimentary, accurately reflecting the great wealth of talent and courage that was present within the labour movement.

Bibliography

3:O232 GIBSON, (John?), Untitled, TS, pp.7 (c.5,000 words). Brunel University Library.

WCML – https://wcml.org.uk

Images

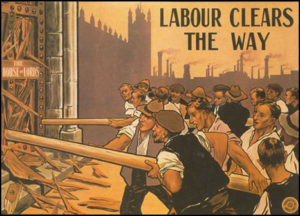

Labour Party poster – http://spartacus-educational.com/Plabour.htm

James Maxton – http://www.universitystory.gla.ac.uk/biography/?id=WH0728&type=P

John Maclean – http://lighthousebookshop.com/event/the-red-the-green-gerard-cairns-on-john-maclean/

David Kirkwood – http://www.theglasgowstory.com/image/?inum=TGSW00056

Leave a Reply