Pauline Wiltshire: Race and Immigration

“There is good and bad in most people, black or white” (Wiltshire, 1985: 6).

Throughout Pauline’s writing, she comments on how coming to England was challenging in terms of adjusting to British culture; her being a black Jamaican woman, she found people did things a lot differently here than they did at home. In her fifth chapter, ‘First impressions of England’, she notes how she was “surprised to see how close the houses were built together”(ibid, 40) yet people here “lived very separate lives” (ibid).

Because Pauline didn’t have a great relationship with her mother and her new family, she found it very hard to adjust to her new surroundings. She was advised to stay at home and not leave the house as she may get lost. For weeks she sat inside her mother’s home while the family were at work and felt extremely isolated, alone and homesick. It could be said that Pauline felt “notions of cultural instability” (Ramone, 2013: np) when she arrived in Britain due to “fragmented and dispersed identities” (ibid) regarding her huge, life-changing move to Britain: a country she is not familiar. Feelings of instability are often found in are privileged in “autobiographical [writing]as well as postcolonial theory and criticism” (ibid) because immigrants often feel lost when they leave their native country for a foreign one. Pauline didn’t receive the support she needed when she first arrived, so felt lost and confused.

However, once she moved out of her mothers family home as I mentioned in previous blog posts, Pauline became a lot more independent and aware of her surroundings. Often, “Migrants – particularly… West Indians – found themselves ‘having to interrogate the lived culture of the colonizers, in order to comprehend their own discrepant experiences’” (Waters, 2018: 10). Pauline grew to love her new home. However, she was never able to forget about her family, and missed her son David greatly. In 1982, she went back to Jamaica on holiday to visit them. She received the “most wonderful welcome” (Wiltshire, 1985: 63) from her son, Aunt Ina and the rest of her friends. Her 3-month trip back to Jamaica was a very intimate and personal trip for Pauline, and so she doesn’t go into too much detail with us, the reader, because it was “just a personal experience and feeling” (ibid:64) for Pauline.

Pauline reflects on how differently her life has changed since she lived in Jamaica, and I get the sense that these reflections only come to her once she visits Jamaica for the first time after leaving. She explains that since she visited Jamaica she now often thinks of the quiet roads there when she is stuck in London traffic, and of how warm the summers are compared to the wet and windy ones in Britain. She also touches upon the fact that she was “one of a majority” (ibid: 65) in Jamaica, “a black girl among very few whites” (ibid). Now, she feels as though she is the opposite: “a black girl amongst mainly whites” (ibid). Pauline explains she will never be able to forget about feeling a sense of isolation in Britain because “there are many white people who imagine that my skin colour makes me inferior to them” (ibid).

I have mentioned throughout my blog posts why Pauline’s autobiographical writing makes a huge, positive contribution to a broader context regarding black women’s memoir writing. Often, black women’s memoir writing breaks boundaries and fills gaps in history that are too often made. Although Pauline is simply talking about her life experiences, feelings, attitudes towards trauma and uncomfortable topics such as disability, race and sexual and physical abuse, her memoirs have become a “public, campaigning function” (Scafe, 2010:134) in the form of writing. By facing racial issues head on, especially during the 1980s, Pauline’s creating forms of authority over her life and how she chooses to see the world.

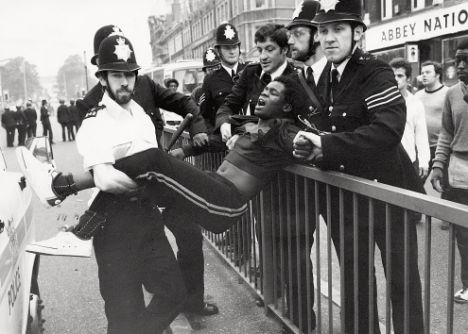

Contextually, “From the second half of the 1960s to the early 1980s marked a new turn in the history of decolonization and black liberation” (Waters, 2018:5). However, “with the failure of black liberation movements in the Caribbean, the shifting politics of radical anticolonialism brought about by the 1979 Iranian Revolution, and the growing differential incorporation of Britain’s ethnic minorities into the structures of the state”(ibid, 13), memoirs like Pauline’s stood as one of many ways black people continued to fight for liberation and equality. Waters notes that black “teachers, writers, publishers, booksellers, campaigners, picketers, marchers, and revolutionaries—were part of transnational anticolonial and civil rights networks” (ibid: 3), fighting for black liberation and equality.

Pauline’s writing certainly falls right in the centre of this movement, confirming her contribution to black memoir writing was extremely important for black peoples and immigrants voices, just like hers, to be heard.

Bibliography:

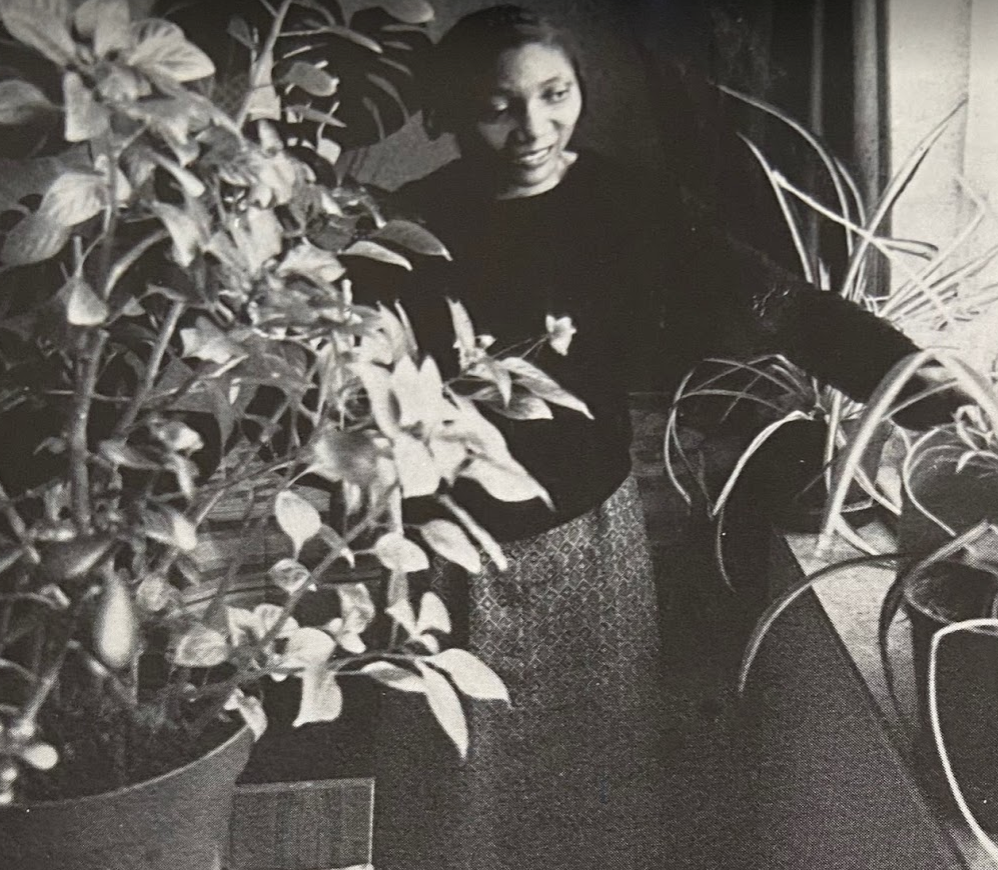

Image 1: Wiltshire, P. (1985). Living and Winning. Hackney: Centerprise Publishers.

Image 2:

Ramone, J. (2013) Vol. 10, No. 1, 1- 3. 2013 Taylor & Francis [Date accessed 14/5/2020).

Scafe, S. (2010) 17.2 129-39. [Date accessed: 14/5/2020]

Waters, R. (2018). . California: University of California Press. [Date accessed: 14/5/2020].

Wiltshire, P. (1985). Living and Winning. Hackney: Centerprise Publishers.

Leave a Reply