Pat O’Mara (1901-1983) Home & Family

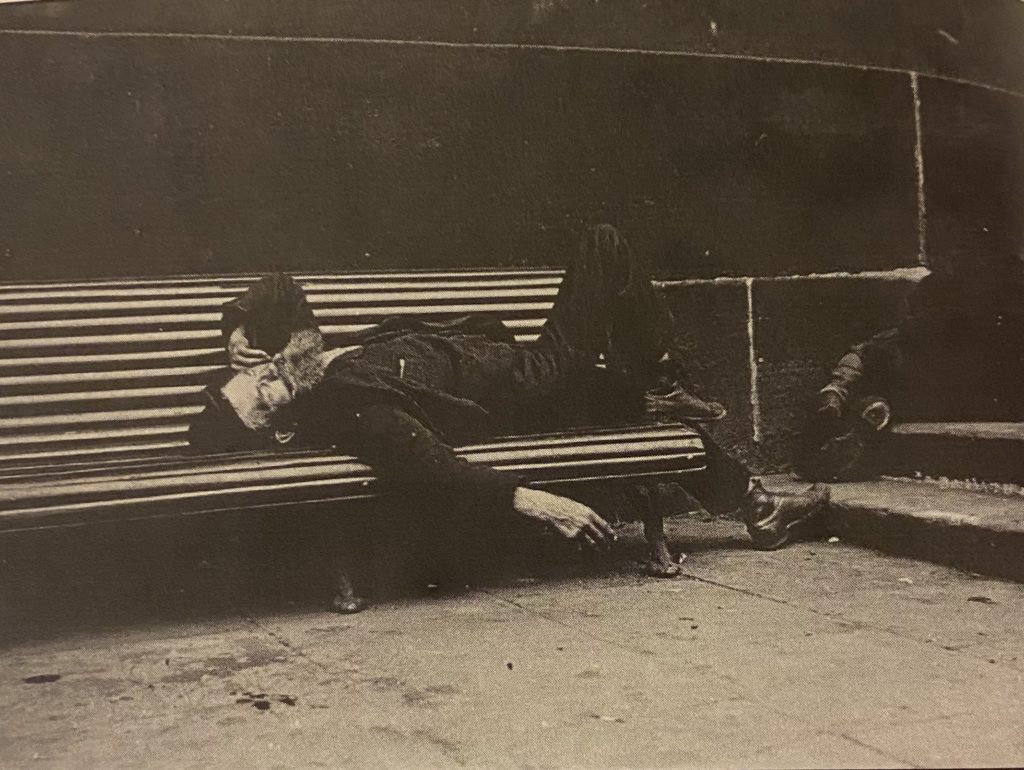

One of Pat’s earliest memories was his mother telling him ‘oh Jesus sufferin’ Christ won’t you take me out of this.’ (O’Mara 20) His mother Mary, father, and sister Alice, were suffering in poverty whilst his mother worked at the Emigrant House and his father spent the family’s money on alcohol. Family life for O’Mara wasn’t a typical family setting as his father spent his time drinking, stealing from his job at the docks or beating up his wife.

Alcohol is a reoccurring theme in Pat’s memoir. Whenever his mother would drink, Pat and Alice would take on the role as parental figures to protect their mother from the perpetual beatings from their father. Pat took the responsibility to care for his mother from an early age and would “counsel” (O’Mara 39) his father. The domestic violence that occurred wasn’t unusual in the slums where Pat lived as ‘the men considered it to be a traditional duty to beat their wives and the wives considered it a traditional penance to accept the continual beatings.’ (O’Mara 23) However, one source reveals that ‘women’s financial dependence, concern for their children and fear of retribution was often the explanation’ as to why they didn’t leave their husbands (Thane 2010). Just like Pat’s mother, leaving her husband would do more harm than good.

During this period ‘little economic help was given to husband-deserters’ (O’Mara 26). This only highlights the poor living conditions Pat was living in at the time as his mother couldn’t afford to leave her children’s father. It shows that if you were born into poverty you would likely die in poverty. Pat’s father seemed to resent his wife because of this and refers to her as a ‘dirty, bloody slummy!’ (O’Mara 93). Pat recognises his father’s dismissal of his wife’s class and understands that social class is something that can define relationships between people.

As a child, Pat recalls how the environment he was living in would result in illnesses and once Pat is spitting ‘yellow, yellow, yellow, followed by blood, strewn all over the floors and walls’ (O’Mara 74), he is sent away to live in Cheshire to recover from his illness. This appears to be a significant moment in Pat’s life once he realises what a ‘wonderful thing’ (O’Mara 75) it is to be living in poor conditions. Although he missed his mother and sister during this time, Pat understood that being away from home and family life meant that he was free, and for once he feels genuinely happy, and a ‘recovery or rediscovery of a new self’ (Gagnier, 1987).

Pat is told that his father has been sent back to jail and Pat’s mother refuses to let him inside the home. The loss of his father doesn’t seem to impact Pat when he returns as he once told his mother ‘I wish my daddy was dead.’ (p87) It becomes apparent that Pat’s father wasn’t a father in his eyes but rather a man who simply drank, stole and abused his mother. Pat’s father wasn’t involved in domestic work or interested in nurturing Pat or Alice, so it is no surprise that Pat feels relieved his father is no longer in his life. Once Pat is working his first job, his father turns up at his mother’s shack and Pat stands up for himself by grabbing an iron kettle and slamming it against his father’s head with ‘all the force at my command’ (O’Mara 99).

Although Pat’s father was an unlikeable man, there is no denying that Pat’s experiences living with him would impact the decisions he would make in the future as he remembers his father in great detail and it’s plausible that Pat’s decision to work at sea was to be someone very different to his father.

Like Pat, memoirist Marion Owen experienced the loss of her father as well but in very different circumstances as shown here by Carina Simi.

Bibliography

Gagnier, Regenia. “Social Atoms: Working-Class Autobiography, Subjectivity, and Gender.” Victorian Studies, vol. 30, no. 3, 1987, pp. 335–363. JSTOR, . p344

O’Mara, Pat. The Autobiography of a Liverpool Slummy. The Bluecoat Press.1997.

Savage, Mike. Social Class in the 21st Century. Pelican. 2015

Thane, P. (2010). Happy families? History and Family Policy. London: The British Academy. P43

Images:

Bellew, Jim & Young, Phil. Whitbread Book of Scouseology. ‘Exley Street, Low Hill’. Volume Two. Merseyside Life 1900-1987. p74

O’Mara, Pat. The Autobiography of a Liverpool Slummy. ‘Sleeping of the affects of drink outside the Custom House (1890’s)’. The Bluecoat Press. 1997. p94

Leave a Reply