Arthur T. Collinson (b. 1893): Home & Family

“United we stand, divided, we fall” (63).

With Arthur T Collinson’s memoir being dedicated to his late Mother, Father, first wife and current wife, it is clear that family were of utmost importance. Collinson’s parents in particular provided the necessary foundation for his initial and further development into a consummate humanitarian, who would one day lead parties and unions that fought for worker’s rights and broader equality. “I dedicate the result to the most loving parents any man ever had and to my girl wife who died a long ago. My gratitude to my wife Geraldine for her love, patience and kindness, which has enabled me to win through” (Foreword).

Collinson’s gratitude towards his late parents is quite telling of his character as during his formative years, the family were poverty-stricken and moved from one slum-dwelling to another before a compassionate consortium – that included the local Reverend – lent a big helping hand; “It was about the year 1903 that the young men’s club of Holy Trinity Church, with the encouragement of the vicar the Rev.J.L.Evans, took a hand in my family’s affairs. They organised a Saturday evening concert in the parish hall and the entire proceeds were handed to a local carpenter to make a newspaper kiosk to start my father in business as a newsagent” (6). This newspaper kiosk was successful for a time and allowed the Collinson family to step beyond the poverty line. With poverty being the reality for most people, the family’s jump out of this was almost unheard of. Indeed, it was witnessing this widespread disparity that helped mould Arthur Collinson’s socialist outlook.

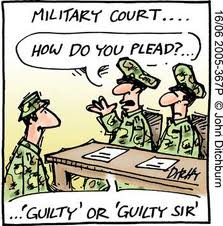

Collinson also had a brother, but he’s rarely mentioned. Instead, the memoir tends to focus on Collinson himself and his constant struggle with real-life, capitalism and all. The mention of family does stretch beyond the foreword though. Collinson’s inclusion in the Great War seemed to provoke certain homesickness and a longing for escape. Feigning the symptoms of worms and other minor ailments were early signals of his intent. Certainly, with war and any sort of violence being at odds with Collinson’s views, his attempted (and failed) desertion was almost inevitable: “I enquired one evening of the sergeant when I would be likely to appear to be charged. He told me that Major Ellis was in constant touch with the hospital, and the base both of were stressing the desertion part of my crime. He gave it as his opinion that I would eventually be court marshalled” (62).

Now, although Collinson’s opposition to war is clear, it was his needy wife that prompted his desire to go AWOL. Collinson wanted to be at home with his wife and their two young girls. The abundant death and destruction had proved too much for a father removed from his family.

In spite of Collinson’s desertion attempt, he was eventually discharged, “My discharge was dated January 30th 1919” (66), and with more pay than he was owed, “with a month’s pay and allowance and thanks to the strange arithmetic at the Army Pay Office, a credit balance, when I was to my calculations pretty deep in debt” (66), and was back on his way to be with his family. The end of 1919, however, was the beginning of much heartbreak for Arthur Collinson; “My parent left us early in the evening on the Boxing Day and the next day my wife was taken ill, and before the day was finished we had another little girl who was prematurely born” (68). Worse still, “On the last day of the year our new baby died” (68).

It wasn’t just the demise of the baby that was a cause of upset, Collinson’s wife had failed to recover from the premature birth; “As I had re-engaged him he attended my wife, whose condition was worsening and after some three or four days she was taken to the infirmary at Homerton, and there on the 26th day of January 1920 she died” (69). From here, the memoir focuses solely on Collinson’s working life. It seems that he never fully-recovered from these atrocities.

Bibliography:

‘Arthur T. Collinson’, in John Burnett, David Mayall and David Vincent eds The Autobiography of the Working Class: An Annotated, Critical Bibliography Brighton: Harvester, 1984, Vol.3, no. 30.

Arthur T. Collinson, ‘One Way Only: An autobiography of an Old-time Trade Unionist’ in Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiography, University of Brunel Library, Special Collection, 3:30

Leave a Reply