Home and Family, James Ashley (b.1833)

Home and family to James Ashley’s are the two most things he holds most dearly within his memoir. James begins his writing after his childhood, in the year 1846, so I have not been able to learn a significant amount about his family as a child. However James does tell the story of an old clock which was passed down the family through generations. The clock was purchased by James’s grandparents when they began housekeeping in 1784, once they passed away it came into possession of James’s mother, however when James’s father got into trouble for not paying the account at the bakery, an incident I spoke about in my introduction post, the clock had to be sold along with the furniture, in order to move house.

“When the trouble came in 1838 and the furniture was for sale the clock was bought by an excise man who lived in the same lane, where in his kitchen I constantly saw it on my to and from the national school.” (Ashley p.2)

Not long after James mentions that the excise man’s house was sold, due to death or some other circumstance, the clock was then bought by a dairyman nearby. Eventually when the dairy was up for sale, the clock was put up for auction and a bidding war pursued between James’s mother and a furniture broker. James’s mother eventually became the highest bidder and gained ownership of the clock once again.

The importance of this story in which James tells me is the meaning behind the clock. This nostalgic style of writing represents the bond his family had as a child, the clock is acting metaphorically as their love. This story I feel holds particular interest, as I believe it emphasizes on the importance of family towards James, which is evident in the way he treats his own family further on in the memoir. Once James had moved to London on 4th May 1856, he spent a large proportion of his time visiting services held by Mr C.H Spurgeon, a British Baptist preacher who had gained a vast amount of popularity in London. It is here in which James Ashley met his wife to be, in which he describes as the most important day of his life. “A little later, early in 1857, there came the most important day in my life.” (Ashley p.11) Through James and Jane’s participation in these preaching services, it is evident that both of them may have derived from a religious background practicing Christianity, which again may resemble the patriarchal structure of a conventional Christian marriage in which they seemingly followed.

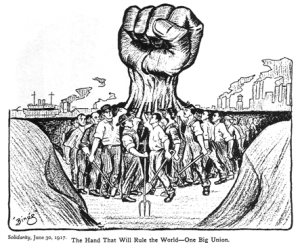

Although I spoke of James’s ability to break stereotypes during his career within my previous post, he alternately follows and abides generic conventions within his marriage. James does not speak at all of Jane’s occupation before the two met, or of an occupation in which she may have undertook during their relationship, instead he draws importance to the domestic virtues in which Jane was responsible for within the home. To me this represents a stereotypical marriage within 19 century England. Women were pushed out of the workplace, first unions for coal miners desired to protect women by banning them from underground work and the labour movement looked to introduce the idea of the ‘bread winner wage’.

This concept fits that of James and Jane Ashley’s marriage; however it would not be accurate to suggest that James was the catalyst for his family’s financial security.

“Yet whilst it is clearly the case that the functions of the family cannot be understood without a detailed knowledge of its structure, the analysis of structure can itself do no more than sketch the shadowy outlines of what actually happened inside the family.” (Vincent p.223)

Throughout his memoir James refers to the importance of his wife within the family home. As James often had to work strenuous hours in order to bring in capital, the roles of a father and husband had to be often neglected, leaving his wife Jane to fill the void left behind.

“My Wife and will, who was then 16 months old, went in June to Wrexham for the summer months and business was so good that year that I could not get away for my holiday and to bring them home until October.” (Ashley p.15)

Within this quote we see James abiding the patriarchal role of a 19th century family. As business was good, he would have to make the sacrifice of not seeing his family, in order to stay at work and bring in capital for the household. A common theme within working class families.

“Until real incomes rose in the later nineteenth century, until family size began to decline and more infants survived, there was little time or space in the working class life for strong emotional investment and children had to take their care in the common struggle for survival” (Burnett p.15)

Not only did Jane provide influence for the duty of care for his children, but also of himself. James’s mentions an incident which occurred during the year 1862, when James’s two sisters came to visit him and Jane. After they had visited common tourist attractions such as Madame Tussauds, they desired to ride an omnibus (Horse-drawn enclosed bus) from Baker Street to the bank.

However due to their only being enough room in the carriage for the women, James offered to ride outside, which would eventually lead to the cause of his illness. “There came a violent storm, I was soon wet to the skin and in a few days was alarmingly ill- I had pneumonia.” (Ashley p.16) Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lungs, which if untreated can be life threatening and with the lack of health care available within the 19th century, James had to rely heavily on his wife Jane to nurse him back to full health, whilst also finding the balance to look after their first born Will. To me this represents a relationship in which one works for the other, if James had died, the economy of their family would have fallen dramatically. Finding an equilibrium between financial and domestic values was obviously the stimulant for their success as a family.

We can now be certain, for instance, that the wife of a domestic artisan was frequently not only her husband’s emotional and sexual partner, but also his business associate. (Vincent p.223)

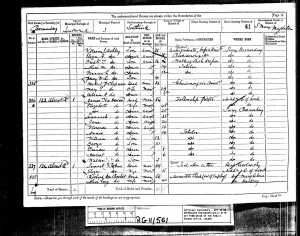

The relationship between James and Jane manifested, with James changing his occupation from a silk hat finisher to a hat shaper, he managed to find greater financial success and throughout the years up to 1870, five more children were added to their family, Lila, Fred, Alice, Louisa and Walter. Throughout James’s memoir I find it somewhat apparent that James possibly favored one of his children more than the rest. When discussing his children’s achievements, he evaluates so much more of his writing to his first born son Will. Will’s highly esteemed achievement of gaining a place at Oxford university was obviously an extremely proud moment within James’s life, as it would be for any parent, especially one who derived from a working class background.

However on page 22 of James’s memoir he informs us of a death within the family, a death of one of his children. “We had five children (Walter had died on Dec. 21, 1871) and we also had my father to think about.” (Ashley p.22) After the death of Walter, James does not deliberate on how the death occurred, or how it impacted him and his family at all. This I thought was strange for someone who I believed was centered on the idealization of family affection. However partly the reason why families were so large within the 19th century was to do with the high rates of infant mortality, people had many children and accepted that not all of them would survive. Nonetheless the idea that James favored Will over the rest of his children is merely based upon slight evidence of the writing within his memoir, of course I am not suggesting that this is in any instance definitively true.

“The most sophisti-cated computer programme can never tell us how much a man loved his wife, to what extent he grieved over the death of a child, nor can it establish with any precision the way in which the fundamental emotional experiences were affected by the material circumstances of the family.” (Vincent p.223)

Bibliography

Burnett, John ed. Destiny Obscure: Autobiographies of Childhood, Education, and Family from the 1820s to the 1920s London: Alan Lane, 1982.

Ashley James, Untitled, pg1-50,(c, 12,500 words). Brunel University Library. Vol:1 No:24

Vincent, David. ‘Love and Death and the Nineteenth-Century Working Class.’ Social History, 5.2 (1980): 223-247

Date Visited- 20/10/14

Leave a Reply