William Wright (b.1846): Home and Family – Part 2

Before reading about William Wright here, make sure you have checked out Part One. It is important to see how much his life changes.

William Wright’s life becomes more independent when he marries: ‘I took a cottage in a part of town known as Rack Close, for two shillings per week. I had been a very careful fellow and had saved enough to make our little home’ (22). At this point, we see William’s independence come through in a more mature and sensible way. Through calling it his ‘little home’, it makes it sound endearing, showing that he looks back on these times fondly.

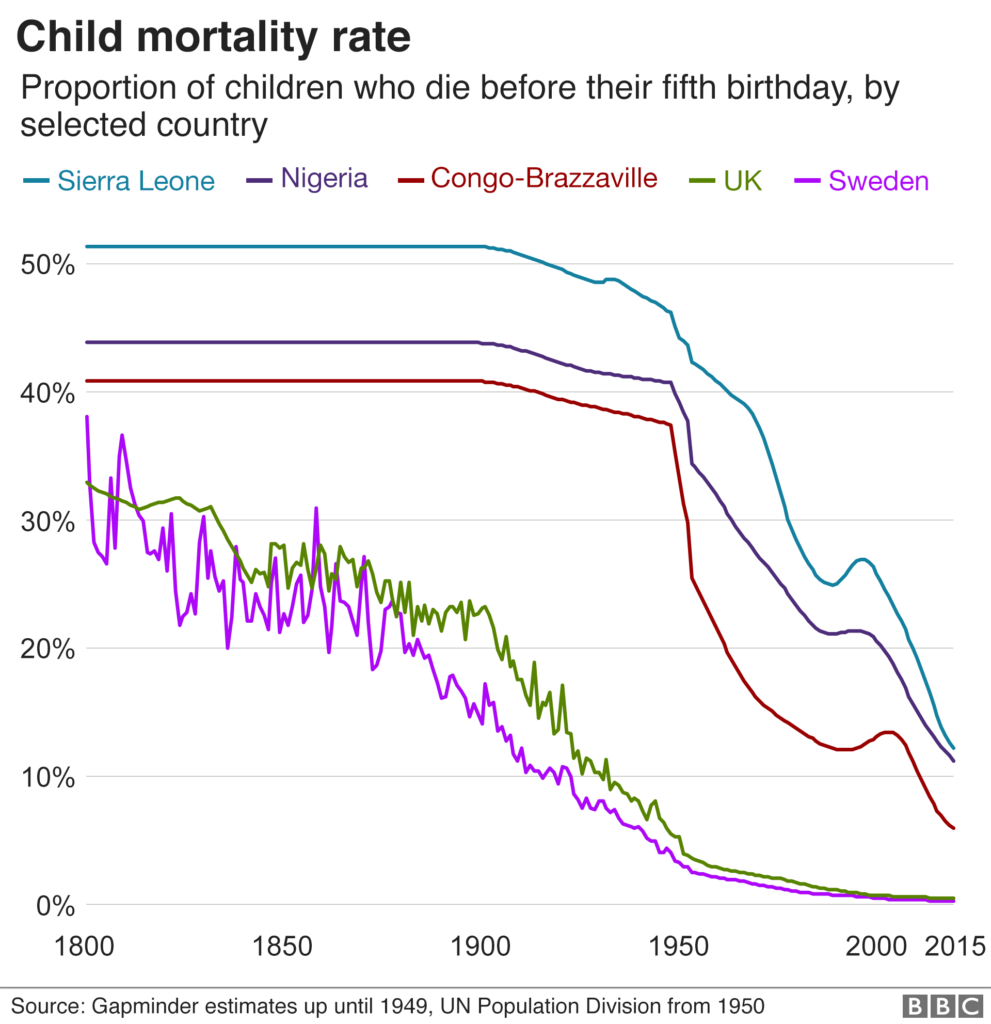

However, his life takes a darker turn. William touches on the subject of child mortality: ‘I took a house in High Street… Then came the first bit of trouble. Our little son passed away at the age of seven months.’ (25). Again, William uses the word ‘little’ in an endearing way, showing his affection towards the first child he lost. It should be noted how casual ‘first bit of trouble’ sounds, but it is important to remember that child mortality was a lot higher than it is nowadays. Child deaths were common in the 19th century. The child mortality rate was so severe that Lionel Rose talks about how someone remembered their teacher ‘would take her ruler and draw an ink line through the child’s name in the register. She would then write a capital ‘D’ at the end of the in line’ (150).

Like his father, William went on to have a large family. As he built the family, William sadly loses another child: ‘But thank God we were blessed with two more boys, George and Gaythorne, and three girls, Ellen, Maud, and Caroline Jessie: the youngest died when only six months old’ (25). This sentence recollects the happiness at first, by saying ‘thank God’ and listing all his children. Then it ends on a sombre note.

We then get a mention of another of William’s siblings, ‘I rented a cottage at Nutford-street, Landport, and gave the business to my brother Henry, who carried it on for many years until he passed away.’ (27) There is a constant reminder of death in these last few pages. It could mean that William’s old age is making him think more about mortality, or it could be that talking about the deaths of the people dearest to him is important, since it would have affected him. It should be noted that David Vincent comments how ‘The most sophisticated computer programme can never tell us how much a man loved his wife, to what extent he grieved over the death of a child’. This should always be considered when reading memoirs which talk about death, because making assumptions about the writer’s emotional state could change how you perceive the rest of the memoir.

Despite this, death continues to plague William, ‘My dear wife died at the age of forty-five years: then I lost my right hand, for she was a good help-mate.’ (35). According to the Office for National Statistics: ‘In 1841 the average newborn girl was not expected to see her 43rd birthday’. While the average lifespan would have been shorter than it is today, William still outlived his first wife by over forty years. It is a long time and he still says ‘I lost my right hand’. This could mean both in terms of helping him with manual labour and the emotional support couples get from one another. Regardless of his reasoning, ‘she was a good help-mate’ does show how dependent he was on her for her work.

William must be used to death at this point, so it is no surprise that he moves on. His writing is not as emotionally attached to his new wife and family, since we don’t get any names: ‘After a time I married again; we had a boy and a girl.’ (35). Notice how he describes this compared to Ellen and the family he had with her? I do not believe it is anything to do with loving them less, but perhaps the death of people in his family makes William want us to know about them more. This makes it so their lives are immortalised in his writing.

Even when his children were in adulthood, William still outlived some of them: ‘as he (George) was ill I took him to Portsmouth Hospital: and brought him back dead after only two weeks. He left a wife and two children which was a rather low blow for me.’ (35) It shows how William never stopped caring for his children. In the following page William sees looking after his family as a task, but a task to be proud of,‘My dear Mother died, so my father came to live with me for seven years. He was eighty-four when he passed away and was laid to rest with his wife; so I did my duty.’ (36). ‘I did my duty’ can be seen as William looking back in pride. Out of everything he did in life, he is glad that he was there for his parents.

Eventually, it was time for one of William’s sons to take on a similar duty: ‘My son took me to a nursing home and in in August I had the operation’ (47). We see how William could not always be the head of the family. This will be talked about more in my next post, Purpose and Audience.

Bibliography:

Wright, William. ‘From chimney-boy to councillor – The Story of my Life’. See John Burnett, David Vincent, David Mayall. The Autobiography of the working class; an annotated critical bibliography. Vol. 1 1790-1900. 1st Pub. 1984. Item: 777.

Secondary Sources:

“How Has Life Expectancy Changed Over Time? – Office For National Statistics”. Ons.Gov.Uk, 2015, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/articles/howhaslifeexpectancychangedovertime/2015-09-09. Accessed 8 Apr 2019.

Rose, Lionel. The Erosion of Childhood Child Oppression in Britain, 1860-1918. Routledge, 1991.

Images used:

BBC News:

West Lothian Council:

Leave a Reply