Life and Labour, James Ashley (b.1833)

Labour within James Ashley’s memoir is a fundamental part of his development throughout his life. James’s memoir mirrors that of a social journey and he uses his labour as a constant reminder as to how hard life was, growing up in 19th century Britain. James instantly took up work straight after school in the year 1850 as an apprentice in silk hat finishing. “1850 that I went to the plank and was put for six months under a practical man to teach me Silk Hat Finishing.” (Ashley pg.3) Life as a child working in the newly industrialized era was difficult, as exploitation and harsh discipline were usually, although not always the case.

“The transition to a capitalist market system and the commodification of labour power that came with it marked a significant intensification in child labour exploitation.” (Lavalett pg.211)

James discusses aspects of his apprenticeship in which he had to partake in, which reflect the usual jobs designated to child labourers within the 19th century.

“For four years I had been in the retail shop and warehouse, serving customers, cutting the plush of various qualities for the covers of hats and putting out the brimmings for lining and binding.” (Ashley pg.3)

Despite detailing this, James Ashley does not deliberate on the emotional side of this labour. He fails to mention any periods of strict discipline or exploitation, which makes it hard for me to gage whether or not his experience of labour as a child was a positive one, or like what most children had, a negative one. However one clue I found within James’s memoir which could imply a negative experience, is that he did not want his first born son Will to go down the same path, instead pushing him to pursue a more intellectual, respected career path.

“In 1875 Will had been placed twenty-third in the general list of the Oxford Local Examination (Junior); in 1876 he gained a good place in the senior Oxford Local, and in 1877, his last Oxford Local Examination he was placed first in all England in History and Literature and fourth in the General list.” (Ashley pg.24)

Will would go on to become the Vice-Principal of the University of Birmingham in 1916 and in June 1917, receive the honour of knighthood. An extremely respected man!

Will’s success I find is inspiring; however it would not have been possible without the continuity of hard and often strenuous hours which James Ashley sacrificed for his labour, so him and his family could enjoy the financial benefits. “I went to business at 6am and continued until 9 and sometimes 10 o’clock at night and frequently earned from £4.10 to £4.15 a week, only once did I exceed £5. (Ashley pg.14) After James had moved to London in the year 1856, his occupation changed from silk hat finishing, to a hat shaper. “When I saw the London men at work I felt confident I could “Serve Turn” and after a little pecuniary arrangement with the foreman of the department I became a Shaper.” (Ashley pg.14)

Demand for manufactured goods rose drastically within the Victorian era, which led to increased demand for workers like James Ashley with particular skills.

“With over 370,000 of its inhabitants in 1851 employed in the manufacturing sector, London was the largest manufacturing town in the country and in Europe.” (Schwartz pg.31)

This change in occupation turned out to be a success for James and in the year 1862, it was clear he had gained a sense of pride within his labour. He was now regarded as one of the best shapers in his business, even shaping the hats of the two business owners to which he worked for. “By this time I had come right to the front and was selected by Mr. George and Mr Alfred Christy to shape the hats for their own wear.” (Ashley pg.15) James’s ability to uphold a profound work ethic was a primary reason for success within his chosen labour.

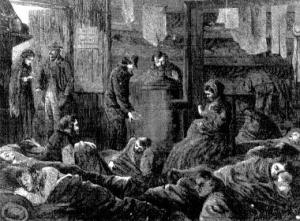

Not only did James dedicate long hours to his position as a hat shaper, he also undertook another job as a teacher in a ragged school. Much like his hat shaping labour, James dedicated the entirety of all he could to his position within the ragged school and yet again he was rewarded for his hard work. “In April 1862 I was asked to be evening master at the Butler Place Ragged School for four evenings a week from 7:15 to 9 o’clock at a salary of £20 a year, and I accepted. It lessened my evening hours in the hat workshop, but I still continue the early morning movement. I began teaching at once.” (Ashley pg.16)

This success in turn brought about a strong sense of pride to James, as his long hours of labour were being rewarded by financial benefits. James had gained a position of financial stability where he could afford to allow his children the right to a private education. “Will had only gone at intervals to a private school; “Lila” (Eliza) was also at a private school, and Fred at the British school.” (Ashley pg.20) This financial support earned by James would help bring about solidarity within the family, constituting towards a good family life. A concept which James holds close to his heart, as like I mentioned in my previous post of home and family, he enjoyed during his time as child.

Much like Leisure within my previous post, labour within 19th century London held a division over society, which separated the population into their respected classes. Capitalist classes such as the bourgeoisie owned and controled means of production, they are your bankers, politicians, aristocrats, landowners etc. Whilst the working class (proletariat) sell their labour in exchange for a weekly wage and have no control over this labour process. However three classes have continually been used throughout scholarly work in order to gain the most accurate reflection of the social order.

“In the era of the Great Exhibition and the mid-Victorian boom, when Britain proclaimed itself the ‘workshop of the world’, there were many who continued to believe that the three-stage model most accurately reflected the social structure of the time”. (Cannadine.Ch.3. III. The ‘Politics of Class’ Denied)

The three stage model has been suggested and deliberated in different ways by different scholars. George Bramwell an English judge who lived during the years 1808-92 declared them as privileged, enlightened and inferior. However Karl Marx’s explanation of the three classes I find is easier to understand, in helping me align a class in which James Ashley truly belonged to during his hours of labour. And if at all, did he work his way up to a position in which his social standings may have changed.

“This enabled him (and his followers) to place everybody in one of three categories: landowners, who drew their unearned income from their estates as rents; bourgeoisie capitalists, who obtained their earned income from their business in the form profits; and proletariat workers, who made their money by selling their labour to their employers in exchange for weekly wages.” (Cannadine.Ch.1.I.Class as History)

Looking at Karl Marx’s grouping of classified individuals, it is clear to see where James Ashley would have been placed. James would fall under the proletariat worker, as he sold his labour, which derived from his skill in hat shaping, to his employers. By doing this James earned a weekly wage to provide for him and his family. Working class labourers were usually associated with places such as pubs and music halls. However make no mistake, this was not James Ashley. What James Ashley represented was the pinnacle of working class respectability; he nurtured his craft within the hat industry in order to gain a position of labour. Once this was achieved, he never once looked back. This sense of achievement and respectability is evident through his presence within the House of Commons.

“From 1857 to 1856 I was many times in the Strangers’ Gallery in the House of Commons: I had special means of access to it, as our frim made all the Police hats from London, my foreman knew all the Police Superintendents and a note to the one on duty at the House of Commons got me easily into the Strangers Gallery.” (Ashley pg.18)

Bibliography

Cannadine David, Class in Britain. London. Penguin Books Ltd. 2000

Michael Lavalett in Marjatta Rahikainen (ed) Centuries of Child Labour: European Experiences from the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century. Aldershot. Ashgate. 2004

Schwarz. L.D, London in the Age of industrialisation: Entrepreneurs, Labour Force and Living Conditions, 1700-1850. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 1992

Ashley James, Untitled, pg1-50,(c, 12,500 words). Brunel University Library. Vol:1 No:24

Leave a Reply