Mabel Florence Lethbridge (1900-1968): War and Memory, Part 1. The Great War

World War 1 The Great War (1914-1918)

” Can anyone imagine the anguish and terror I experienced when I realised that my leg had been blown off, and I held in my tortured hands the dripping thigh and knee”

(Lethbridge – P.82)

When the Great War broke out in 1914, Fourteen-year-old Mabel was living in County Cork, Ireland with her mother and two brothers Reggie and Leghe. Because of Mabel’s wasting disease they had moved to Peake House in 1909, a large rambling country house with a hay loft and outhouses where Mabel could play and get well. Life for the Lethbridge family was a far cry from the war raging across Europe.

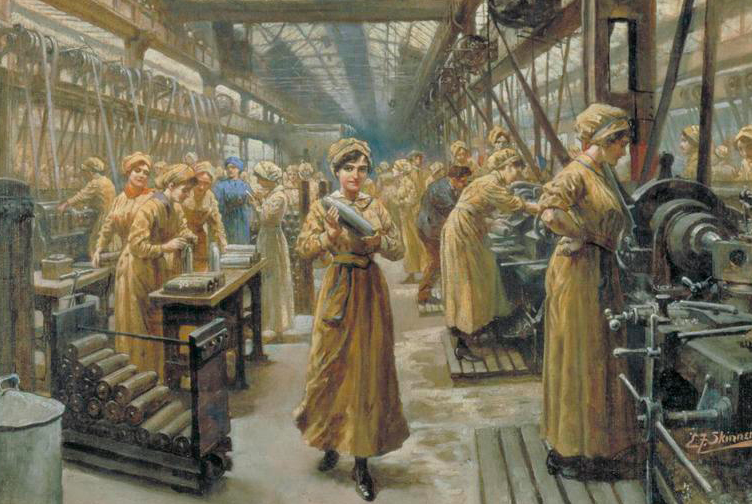

At the age of fifteen Mabel left Ireland to return to London. As headstrong as ever Mabel’s mother likened her daughter to a factory girl. Her mother’s upper-class values were challenged as Mabel announced, “I wish to Christ I was a factory girl!” (p.22). Little did she know that two years later her wish would come true with devastating consequences.

In 1917 Mabel took a job in Bradford Royal Eye and Ear Hospital as a probationary nurse. After she successfully completed a month’s trial she was put on night duty on the soldier’s wards where she ‘found herself brought face to face with war’ (p.35). Mabel’s mother intervened and after eight short months her nursing days were over. Heartened by her experience and as positive as ever, Mabel felt a great sense of independence and was more determined than ever to do her bit for the home front. Her next job would last for only nine days and change her life dramatically.

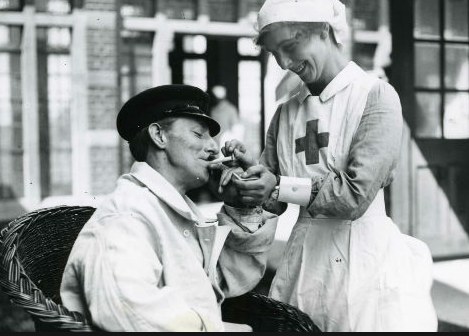

First World War Red Cross nurse lights a cigarette for a patient

Despite having lied about her age to her family and the authorities, Mabel started work at Hayes National Filling Factory where she volunteered to work in the Danger Zone. Fearlessly, working on condemned ‘monkey machines’ Mabel adapted to making shells with Amatol and T.N.T. Despite the backbreaking work she writes of the camaraderie between the women and the friendships she made. Then on 23rd October 1917, Mabel was the only survivor of a catastrophic explosion. The description is graphic and visceral as she describes the smell of burning flesh and her blackened hands. Mabel recounts the harrowing after effects of T.N.T poisoning and temporary blindness. See for Mabel telling her story to the BBC. But, as strong willed as ever, she refused to become an invalid and was determined to regain her independence.

In contrast to Mabel’s devastating account of what happened Muriel Dayrell-Browning while working at the war office in September 1914 wrote a letter to her mother ‘Then we saw it was the Zepp diving head first. That was a sight, cheers thundered all round us from every direction, it was magnificent the most thrilling scene imaginable’ (Higonnet.p.255) The war had created opportunities for women, including Mabel who saw a chance to unshackle themselves from the home.

The German zeppelin night raids of WW1 inflicted terror on London

It is credit to Mabel’s strength of character that she has written this memoir which predominately focuses on the explosion that nearly killed her. Recalling the events leading up to the accident must have been arduous. Suffering the agonies of traumatic memory are discussed in life narratives of disability narrators who struggle to find ways of telling their experience. (Smith.Watson. p.22)

Mabel was recognized for her bravery by the King who bestowed upon her the medal of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (p.105). On the 1st January 1918, she was featured in The Times newspaper “for courage and high example shown on the occasion of an explosion during which she lost a leg and sustained severe injuries” (p.105). The honor is outweighed by the irony of her not being eligible for a pension. Mabel never voices her political thoughts but keeps the reader updated with her battle for compensation.

Mabel’s writing is confessional but certainly not unstructured. The dominant tone overall is lyrical but as Mabel recounts her brother Leghe leaving for France she adopts an elegiac tone. She also writes solemnly at the sight of the wounded and dying she saw being stretchered out of Charing Cross station. Sadly she recalls ‘The real significance of war striking coldly at my heart’ (p.37).

Autobiographical writing falls into specific categories ‘in which women writers outnumber men, are characterized by a kind of aimless, unstructured writing that I call confessional in the sense of “true confession,” (Gagnier .355). Mabel is the exception, her writing flows poetically and always from her heart.

Despite the physical challenges, Mabel’s will grew stronger and once again she locked horns with her mother. An officer from the front had seen her picture in The Daily Mirror and Mabel, against her mother’s wishes, had began corresponding with him. In a fortunate stroke of serendipity, her accident had brought Mabel unexpected romance with a man she called “Daddy”. (see Life and Labour Part 2)

Sources:

Gagnier, Regenia. ‘Working-Class Autobiography, Subjectivity, and Gender.’ Victorian Studies 30.3 (1987): 335-363

Higonnet, M. R. Lines of Fire : Women Writers of World War I New York: Plume(1999)

Lethbridge, Mabel. Fortune Grass, Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiographies, University of Brunel Library, Special Collection Library, Vol.4

Smith, Watson, and Watson, Julia. Reading Autobiography a Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives. 2nd ed. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota, 2010. Web.

The German zeppelin night raids of WW1 inflicted terror on London and presented stiff challenges for

Leave a Reply