Nora Isabel Adnams: Purpose and Audience

‘Well, Husband of mine and you, my children, this is the end of six and a half years of your old “Mum’s” memoirs in Dr. Barnardo’s Homes.’ (26)

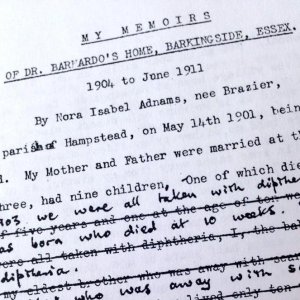

Nora Isabel Adnams’ memoir spans over a relatively short period of time, discussing her childhood years at Barkingside Village Homes for Girls. The audience and purpose of the piece can be determined throughout Nora’s work as she speaks directly to the reader on several occasions and raises a lot of interesting points along the way. The memoir is penned many years after Nora’s time in Barnardo’s home, as we learn she now has both a husband and children. This gives the piece a slightly nostalgic tone, and may suggest she uses her writing to reflect on times gone by.

The first thing that’s important to remember is that Nora is only 3 years old when she is first taken to the Barnardo’s home. As a result, she is quick to point out that ‘these things were either told to me by my eldest sister, or otherwise are my own memories’ (2). This suggests that although one of the purposes of this autobiography is to share her memories, Nora needs some help along with the finer details, meaning not all of these stories may be 100% accurate as ‘things strike different people in different ways’ (2).

The audience of the autobiography is Nora’s family, as she directly addresses both her husband and children. Nora refers to herself as ‘your old “Mum”’ (26), and this may explain the piece’s interesting tone. Nora is confident and conversational in her writing style throughout which contradicts with some of the critical assumptions about working-class writing. Critics have stated that working class autobiographies often seem self-conscious as ‘being a significant agent worthy of the regard of other … was not a given’ (Gagnier, 338), but this is certainly not the case in Nora’s memoir. She is clearly at ease writing for her family and this makes the piece feel heartfelt and sincere. Her tone also makes the memoir accessible to a much wider audience than Nora originally intended as a result of this.

On the surface, the purpose of the piece could be for Nora to share anecdotes from her childhood with her family. She tells many stories, that may have been omitted had the story been published for a commercial market, so the idea that the piece is solely for family use makes sense. This would also fit with Gagnier’s idea that working-class autobiographies tend to be ‘functional rather than aesthetic: to record lost experiences for future generations’ (Gagnier, 342).

On a deeper level, however, the memoir could be seen to comment upon class and upbringing, which may suggest another motive; to educate and inspire others. This could show that Nora’s purpose is more in line with Hackett’s idea that ‘working-class autobiographers justified their excursion into a literary genre by claiming they wrote social history’ (209), as she uses her own experiences to comment on the much larger problems in society. For example, Nora is very keen to stress the importance of wealth to her family, but also the fact that they should share this wealth with those less fortunate; ‘So you, my dear children, if at any time it lays in your power to help a child in need, do so, for your poor old mum’s sake’ (17). This could suggest that Nora’s piece not only represents her own voice, but also the voice of others who find themselves in poverty or unfortunate circumstances, as she wishes for a positive outcome from her autobiography.

To conclude, although Nora originally intended for her autobiography to remain within her family home, the style and tone allow for it to be enjoyed by the public as well. She uses her own experiences to comment on the world at large, and provide hope for other working-class people.

‘Nora Isabel Adnams’, ‘MY MEMOIRS OF DR. BARNARDO’S HOME, BARKINGSIDE, ESSEX’, , University of Brunel Library, Special Collection: 2:859

Hackett, Nan. ‘A Different Form of “Self”: Narrative Style in British Nineteenth-Century Working-class Autobiography’. 12.3 (1989): p. 209.

Gagnier, Regenia. ‘Social Atoms: Working-Class Autobiography, Subjectivity, and Gender.’ Victorian Studies, 30. 3 (1987), 335-363

Leave a Reply