Wilhelmina Tobias: Purpose and Audience

The classic autobiography was, for many years, the preserve of the famous and the middle classes. Autobiographies by acclaimed writers include details of contemplation of the individual self, self-reflection and aim at establishing the difference between the writer and the reader. Improved levels of literacy in the working classes combined with increased access to literature meant that memoirs and autobiographies by members of the working classes became much more commonplace. Regenia Gagnier studied a number of memoirs for an article dealing with identity and subjectivity in working-class life writing. These working-class memoirs differed from classic autobiographies in common ways and shared common narrative structures which Gagnier placed into six types “…conversion and gallows narratives, vestigial religious forms found most often in the provinces by the nineteenth century; commemorative stories, largely by southern agrarian, domestic, and itinerant workers; political or polemical narratives by authors with organized political bases, largely from the industrial North; confessions – in the popular sense of “true confessions” – more often by women, sensational, and usually for London audiences; and therapeutically-motivated self-examinations” (Gagnier, 1991 p155)

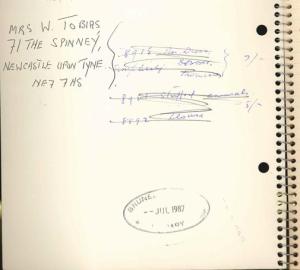

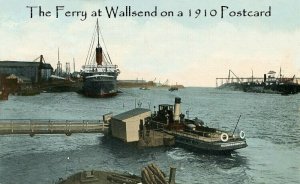

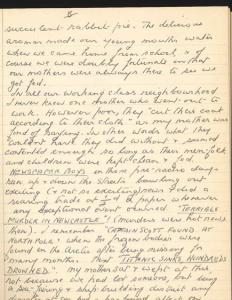

Wilhelmina Tobias memoir is unlike many working class autobiographies in that it only addresses a very limited time in her life and the narrative structure is hard to define using Gagnier’s parameters. Born in 1904, the memoir covers Wilhelmina’s childhood up until the start of the First World War in 1914. It mixes recollections of specific memories and events, such as the sinking of the Titanic and the death of Lord Kitchener, with descriptions of family and street customs, such as Washing Day and visits from the fish and vegetable men. This is most like the commemorative stories narrative defined by Gagnier which ‘…present unstructured, thematically arbitrary, disconnected anecdotes and events of a world in which nothing changes. There are no distinctive autobiographical subjects apart from the continuous life of the village, farm, or crafts-mystery, and no Other but the future that will end this way of life’ (Gagnier, p156) However, other elements, such as the passage about her father’s political activism, have a political or polemic narrative, which Gagnier describes as ‘The opposite form to the storyteller’s [narrative]’ and creates an interesting juxtaposition.

Due to the time period covered by the memoir, it contains very little detail of Wilhelmina’s life and reveals very little of her opinions or thoughts. There are no details of any interests or activities that she partook in her childhood, whilst she was too young to have held any occupations or part time jobs. Nan Hackett, who studied narrative styles in working-class autobiographies in her article, ‘A Different Form of “Self”: Narrative Style in British Nineteenth-Century Working-class Autobiography’ wrote that ‘even in this very personal, subjective, and supposedly egocentric genre, the “I” is minimized and even depersonalized.’ (Hackett, 1989 p210) In Wilhemena’s case, the I has become so depersonalised there is barely any personal or egocentric elements to the memoir.

The memoir’s lack of personal details or opinion also echoes Gagnier’s claims in ‘Working-Class Autobiography, Subjectivity, and Gender’ that ‘Most working-class autobiographies begin not with a family lineage or a birthdate but rather with an apology for their authors’ ordinariness, encoded in titles like One of the Multitude (1911) by George Acorn’ (Gagnier p 338) This is indicative of the author’s perceived lack of status within the literary world and highlights their previous experience with published autobiographies written by celebrities or luminaries who had led colourful lives. She also states that ‘For working-class auto-biographers. . . subjectivity – being a significant agent worthy of the regard of others, a human subject as well as an individuated “ego,” or I for oneself, distinct from others – was not a given. In conditions of long work hours, crowded housing, and inadequate light, it was difficult enough for them to contemplate themselves, but they had also to justify themselves as writers worthy of the attention of others.’ (Gagnier p.141) This is a problem for many working class autobiographers though Wilhelmina doesn’t address or apologise for this like many others and instead begins her memoir with her birth date and her earliest memory. Wilhelmina has no trouble using the historical I, but clearly struggles with the idea that her life and opinion are relevant and instead recounts societal observations with little to no detail.

Wilhelmina’s memoir can be associated with Nan Hackett’s statement that autobiographies were ‘primarily “testimonial”; its purpose was to document a way of life’ in that she is documenting the events and customs that she remembers from her childhood in an effort to, as Gagnier describes, ‘…record lost experiences for future generations’ (p.39). The memoir also, from the first recollection, identifies itself with the working classes. Hackett writes that working-class authors ‘insisted on identifying themselves as members of the working class, no matter what later success or wealth they enjoyed.’ This is true of Wilhelmina’s memoir, which references her background on a number of occasions as well as documenting the social history of the reality of living in such conditions.

Wilhelmina makes no effort to address the reasons or motivations behind her decision to write a memoir so we as the reader have to try and infer some reasoning. This results in a more in depth investigation into the motivations of working class autobiographers and leads to a better understanding of the elements that resulted in the working classes writing about their lives. Wilhelmina’s effort to preserve the memory of her childhood for later generations is a prime example of the efforts a newly literate working class went to document their way of life.

Works cited

Gagnier, R. (1991) Subjectivities : A History of Self-Representation in Britain, 1832-1920: A History of Self-Representation in Britain, 1832-1920, Oxford University Press

Hackett, N. (1989) A Different Form of “Self”: Narrative Style in British Nineteenth-Century Working-class Autobiography

Burnett, John, David Mayall and David Vincent eds The Autobiography of the Working Class: An Annotated, Critical Bibliography vol. 2. Brighton: Harvester, 1987. TOBIAS W 2-766

Leave a Reply