Margaret Watson (b.1907) Introduction

“In spite of my many hard times I would not have my life any other way.”

In 1912, when she was just five years old, Margaret Watson was sent to live with her grandparents in Paisley, Scotland following the death of her mother. In her memoir, Margaret recalls how this unwelcome separation from her father – a night shift worker at their local Power Station – was arranged by her grandmother so that she and her brother, Chick, could be “taught to live like respectable citizens, not like heathens” (p.1). One of the things I found fascinating about Margaret’s story is how it shows class divisions within one family. Her detailed recollections of the difficulties she experienced as a child moving back and forth between two conflicting classes makes Margaret’s memoir an insightful and compelling read.

In 1914, only about 20% of Britain’s population was middle class. You would therefore expect Margaret’s rags-to-riches story to be recalled with endless happy memories. However, Margaret’s autobiography is not a typical account that would be expected of a working-class girl living a middle-class life in the early twentieth century. With a few exceptions that made her feel “like a princess” (p.2) after life in her tenement home in Glasgow- like having a toilet in the house without “pee running out under the door” (p.2)- Margaret recalls her social transcendence as a difficult time in her childhood.

Reminiscing on her difficulty to adapt to life in her new “posh” school (p.2) Margaret’s memoir is a reflective piece of writing that describes a child’s struggle with class identity. Viewed by herself, as well as by her classmates, as “not very clever”, Margaret recalls how as a child, she often felt like a “stranger” (p.2). Her memories of feeling uncomfortable in her school uniform may be related to the insecurities she recalled having as a child, always uncertain of where she belonged in society; “With my black and white checked frock, straw hat, this tied with elastic under my chin, almost cutting my head off. The hat made me scratch” (p.3).

When reading Margaret’s memoir, I found it interesting to note the loss of freedom that accompanied her transition into middle-class life. The difference between her memories of Glasgow at the beginning of her memoir, where she and Chick would play “grubbily” in the yard (p.1), differs from how the pair would play in Paisley; “Everyday [we] went down to sit on that hard seat on the promenade… We were never allowed to go down to the beach. There we sat, watched the world go by” (p.3). In order to satisfy their Grandmother’s desire for them to be civilised, Margaret and her brother could no longer play without restraint or concern for their appearance.

The remarriage of Margaret’s father in 1914 – when Margaret was eight years old – resulted in her return to Glasgow and her old working-class life. However, she recalls how the happiness of her long-awaited reunion with her father was short-lived; her father, a reserve, was called up in the First World War, and she and Chick were left in the care of their “hated” stepmother, who “drank a lot” (p.5). From then on, Margaret’s memoir revisits her memories of growing up without her parents, and her efforts to change her situation and create a better future for herself.

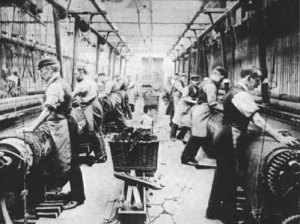

I was drawn to Margaret Watson because her story reads as an example of the growing confidence of women during the early 1900s. In the previous century, as discussed by Jonathan Rose, ‘only one in ten nineteenth-century workers’ memoirs were written by women’ (Rose, 51). The time Margaret spent in Paisley as a child inspired her to strive for a better life for herself and her own children. Her memoir recalls her progress from leaving school at fourteen to work at a carpet factory, “a dirty nasty job” (p.11) to working as a chauffeur for the local council, driving doctors, nurses and midwives (p.31). It was Margaret’s ambition and her refusal to settle for what was considered the ‘norm’ for the working-class woman that I admired throughout reading her story.

Although Margaret’s memoir addresses her hardships, her account of life in the early twentieth century is almost a celebration of the working-class community and the support it offers to those within it. She does not dwell on the unhappiness of her childhood, nor does she complain about the struggles she faces throughout her life. Instead, Margaret considers herself blessed to be a part of the labouring class; a class that provided her with the family she needed when she had none. In the closing passage of her memoir, Margaret writes of the importance of the working-class community to her; “I have very dear friends and neighbours who help me in countless ways. We have not a palatial residence but it is my home” (p.39).

Burnett, John. Mayall, David and Vincent, David (eds) The Autobiography of the Working Class: An Annotated, Critical Bibliography (Brighton: Harvester,1897) Vol: 2 No: 802.

Rose, Jonathan. Rereading the English Common Reader: A Preface to a History of Audiences. Journal of the History of Ideas. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992.

Image References:

A Photograph taken of Cowcaddens Street in Glasgow. Date Accessed: 29th September 2014.

The Old Bridge and Terrace in Paisley. Date Accessed: 26th September 2014

Hand Loom Weavers in Templeton’s Carpet Factory. Date Accessed: 26th September 2014

Leave a Reply