William Wright (b.1846): Class Matters – Part 1

‘I helped my father until I was fourteen years old’ (16).

I have touched on this quote before, but here we can see that William saying ‘I helped’ could mean his work was also a favour. Since he grew up in a working-class family, William knew that his father required extra hands to do more work, which in turn meant more money.

Lionel Rose touches on this when saying, ‘In large poor families their value was primarily economic, and in domestic workshops parents could be harder and more ruthless than a large factory employer’ (215). William does mention he came from a large family, and this notion that a child’s ‘value was primarily economic’ can fit into the ideas I am exploring, as I try to look into different reasons William worked at such a young age. However, there is never a hint that William’s father could be ‘harder and more ruthless than a large factory employer’, so breaking from his working-class background would not have had anything to do with his father’s behaviour.

Even though William does eventually break out of the working class bubble, there will always be something which reminds him of his humble beginnings: ‘An iron chisel had cut my right-hand middle finger to the bone. I still have the mark of the cut on my finger’ (9-10). Even when he breaks through the working-class barrier, he is still reminded of a mark, caused from the days he was part of the working-class.

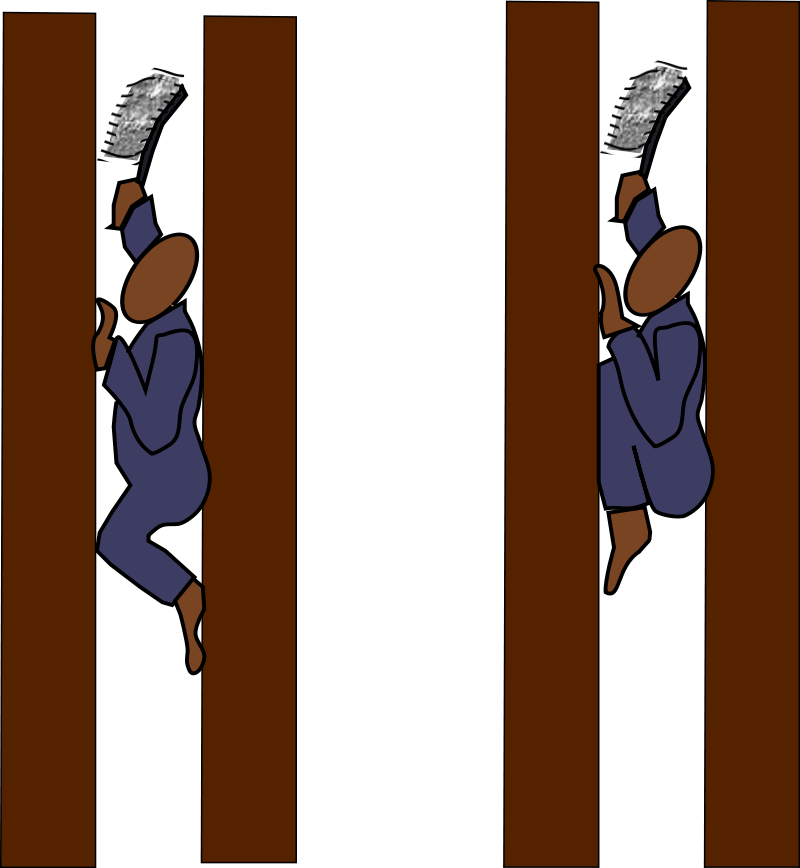

Similarly, William touches on an issue that is still relevant today. We are given insight to the health and safety of chimney sweepers: ‘But it was an expense to take it down and brick it up again. So the foreman of the Mills said to Father, “Your boy can get over the bridge.”‘ (13). Of course, today’s health and safety standards are a lot tighter and many businesses do look out for their employees, but it is still an issue. According to Health and Safety Executive, ‘555,000 injuries occurred at work according to the Labour Force Survey’ in 2017/18. It can be argued that Victorian attitudes meant that William’s class made him appear as less to others: ‘But the pain was enough to have killed me and more dead than alive I had to carry on and clean the flues’ (14). Even through severe injury, William still had to work.

When William wants to start a new life, his choice is ‘to run away to sea’ (17). Perhaps this shows how people who came from poorer backgrounds lacked the skills to explore other alternatives on land. This is backed up when he cannot even escape the type of career he had been so accustomed to: ‘He then asked me what I had been, and when I said a chimney sweep and climbing boy he replied, “Come home with me. I am a master sweep…”‘ (18). It seems, at this point, William’s only purpose is to be a chimney sweep. Even when he explored new opportunities, he was reminded at one of very few things he was good at.

We then come back to the idea of William knowing what he was doing: ‘I said, “Be sharp! I am only going to climb ten. Up one and down the other!” That surprised him. “That’s not the first time you have done that!” he said’ (19). Despite being working-class he could surprise people by how knowledgeable he was in his line of work. ‘I spoke to my master about going: he said he could spare me as his nephew in Ventnor wanted to come and work for him’ (21). This shows how William was disposable, at first. This could strengthen his reason for approaching different types of jobs, especially when he marries. This also acts like a commentary to many issues that are present nowadays. We are currently in a situation where working-class jobs are constantly being undermined and threatened, for instance through the growth of machinery and robotics.

Even though he may appear disposable as an adolescent, William soon proves that he is more than capable of learning new skills. This gives him the opportunity to finally break through his class bubble.

Read part two here.

Bibliography:

Wright, William. ‘From chimney-boy to councillor – The Story of my Life’. See John Burnett, David Vincent, David Mayall. The Autobiography of the working class; an annotated critical bibliography. Vol. 1 1790-1900. 1st Pub. 1984. Item: 777.

Secondary:

Rose, Lionel. The Erosion of Childhood : Childhood in Britain 1860-1918, Routledge, 2002. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ljmu/detail.action?docID=169048.

Health and Safety Statistics, Health and Safety Executive, 2018, www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/.

Images used:

Factory Skyline, found on .

Chimney Sweep stuck, found on . Copyright by 3.0

Leave a Reply