Guy Oates (1905-1987): Education and Schooling- Part One

Being educated at my particular charity school, my learning was slow and poor, and my vocabulary is small- hence the small words I use in this writing. However, I have always felt that my school years were a little exceptional. The few people to whom I have at times mentioned a few happenings have always appeared interested- but this may have been that those listening were polite, and happy to let an old man talk’

(Oates, 1:63).

Castle Yard School

It is fair to say that Guy did not have the easiest start to his school life, and despite his mother’s best efforts, his early education resulted in minimal literacy and numeracy skills. His experience is a stark contrast to the ‘6,000,000 children at school taught by 150,000 teachers, basic literacy and numeracy’ (Burnett, 1982, Pg. 148). Although, evidence of ‘the achievements of elementary education were immense’ (Burnett, 1982, Pg. 148), and can be seen in an array of working-class memoirs. However. Guy’s memoir tends to focuses more on the possible ‘defects and limitations’ (Burnett, 1982, Pg. 148) of the education system, although, they concern themselves more with the treatment of children, and less on the academic success of the system. If you are familiar with part one of the Fun and Festivities blog post, you will know that Guy often played truant from school during his early childhood, and instead, he spent his days visiting ‘Mr Blakely’s market garden’ (1:101), which could be found at the bottom of Guy’s garden at ‘126 High Street, Knaresborough’ (1:105). However, we do not know what caused Guy to have such an aversion to school, or when the problem of truancy started. Therefore, it is important that we begin with Guy’s first experience of education and the school environment.

Mr Blakely in his garden (1:106).

In 1910, at the age of five, Guy began attending Castle Yard School in Knaresborough, under the supervision of ‘the two Miss Southwells’ (1:101). The women, who many referred to as ‘the two sweet ladies’ were in their early fifties, and had been teaching at the school for many years. Their reputation was so pleasant that even Guy’s mother, Phoebe, assured him that they were ‘kind and gentle’ women, whom ‘all the children loved’ (1:101). However, Guy witnessed a very different side to the women during his first day of school, which ‘proved to be a disaster’ (1:101), when he became restless while struggling with ‘the idea of being shut in after running wild, and being expected to sit still for long periods’ (1:101). Guy insists that the real trouble started when he was ‘sat in one of those double wooden desks with a silly little girl’ (1:101), who he claims ‘brought the worst out’ in him (1:101). Within one hour, he had become curious of his partner, and ‘for some reason unknown to him’ he was, ‘seen by one of the Miss Southwells’ with his ‘hand up this little girl’s dress’ (1:101). Though Guy did not understand it, it was, and still is, completely normal for a 5-year-old child to become curious about the body, and the difference between boys and girls. Nowadays, this usually results in a discussion about acceptable behaviours, privacy, and a 5-year-old friendly chat about the birds and the bees. However, society’s attitudes towards this type of curiosity were very different in 1910. After all, Freudian theory was still relatively innovative, and unlikely to be a hot topic of conversation amongst the working-class in Yorkshire. Unfortunately, this meant that Guy experienced a very different response from his teachers, and ‘within a flash this old teacher lady was as nimble as a cat,’ dragging him from his desk, as ‘the other Miss Southwell appeared from nowhere’ and ‘flung’ Guy across a chair. (1:101). With his ‘face turned to the floor (. . .) one of them sat on [him]. With no loss of time, the strap was produced from somewhere and in seconds, [he] was feeling the pain of that strap. Those two sweet old ladies were now two snarling vicious women with the strength of men’ (1:101). He goes on to explain that he was ‘held as if in a vice, the strokes of that strap bringing up weals (welts) on [his] bare legs. Nothing like this had ever happened here before. When they thought [he] had had enough the one sitting on [him] got off’ (1:101). Once he was free, Guy ‘rolled off the chair and rushed into the cloak room grabbing [his] cap and ran away avoiding the High Street in case a Policeman should see’ him (1:101). For a boy of five years old, who had had his ‘own way for the last years’ (1:101) following his father’s death, this chastisement came as a huge shock. Understandably, after such a traumatic introduction to education, Guy developed an aversion to his school, and found himself running away at every opportunity and becoming a ‘truanter’ (1:101). Regrettably, this meant that Guy did not learn to read or write during his early education, and though this did not concern him initially, he went on to understand the importance of these skills and the affect that they could have on one’s life.

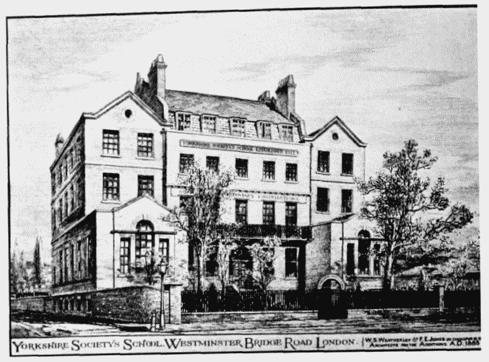

The Yorkshire Society School

In 1913, Guy’s older brother Septimus (Sep) attended The Yorkshire Society School in London, after the well to do family friend, Mrs Bailey, offered to help Guy’s mother (Phoebe), who was struggling financially following the death of her husband in 1909. In her attempts to help, Mrs Bailey told Phoebe that she knew of ‘a charity school in London which accepted boys from Yorkshire only, who were orphans or half orphans. Their parents must be respected people in poor circumstances or having fallen on hard times’ (1:123). However, simply meeting these requirements was not enough to secure a place within the school, and alongside this, the entry requirements specified that students must be ‘recommended and backed by a sum of not less than £400. This being the sum calculated to house, feed, clothe and educate a boy over a period of seven years, nine to sixteen’ (1:123). Having known the family well during their prosperous times, and understanding the level of respect for them within the community, Mrs Bailey believed that ‘she would have little trouble in collecting the sum required, to submit’ Sep (1:123). After some discussion between Mrs Bailey and Phoebe, it was decided that ‘if the amount necessary was collected he be allowed to go’ (1:123). Although, the reality of Sep leaving was difficult for Guy’s mother who was being asked ‘to part with just one child for one whole year, to a school two hundred miles away, and to which she knew nothing about’ (1:123). To make matters worse, the school was in ‘London of all places the capital city, where the tales one heard were a little frightening, and that child was only a child of nine years old’ (1:123). While writing this section of his memoir it seems that Guy had some concerns over the potential judgement of his mother, and turning his attention to ‘all the mothers who may read this’ he asks, ‘what would you have done?’ (1:123). Returning to the story, he talks of his mother’s willingness to ‘put aside the happiness she would retain by keeping him and thought only for the boy and his future, hoping he would be cared for and receive a good education’ (1:123). Despite her obvious understanding of the benefits for Sep, it must have been incredibly hard for Phoebe, who was devoted to her family and spent the entirety of her life making sure they remained close. Even in her final moments, she was concerned that her family would grow apart without her, and she begged Guy to make sure that this did not happen. Her ability to overcome this and live with the reality of Sep’s departure, and ongoing absence from the home, is a testament to the type of woman and mother she was.

Sep left for school in September 1913, and would only return for Christmas and summer holidays, during which ‘he said very little about the school and would break down and cry’ (1:123) as term time grew closer. Clearly, Sep was having some difficulty settling in and being away from his family, and as his wellbeing did not improve while at home, it seems unlikely that homesickness would have been the cause. Nevertheless, Sep prepared to return to school, and as he did, it dawned on Guy that his ‘clothes had all been marked and packed along with Sep’s in a black fairly large metal black box’ (1:123). Alongside their clothes, their mother had also packed ‘some pots of black berry and apple jam, a tin of syrup and a currant loaf’ (1:123). Feeling confused by the contents of the box, and searching for an explanation, Guy discovered that it would not be long before he understood the cause of his brother’s anguish, as he ‘was going back with Sep. To this school’ (1:123). Unsurprisingly, given the level of respect and wealth that his family once possessed, Mrs Bailey had been incredibly successful in her attempts to raise the £400 to send Sep to school. In fact, ‘people had been so generous, that she had collected over £1000’ (1:123), meaning Guy would be able to receive an education too. Once again, this was very difficult for his mother, who was already worried about Sep and the effects that the school may be having on him. Although, Guy reflects that ‘one would have thought with all the trouble [he] had caused and was still causing her decision would have been easy, if only to get [him] away from those pals of [his]’ (1:123). As difficult as this was for Phoebe, she once again put the needs of her children above her own, and allowed Guy to attend the school.

In September 1914, Guy, his mother, his older sister, and Sep, arrived at Harrogate station, where the ‘two little boys, bewildered at all the rush and bustle, knowing little of what lied ahead,’ (1:124) bid an emotional farewell to their mother and sister, as the women ran alongside the train. As they faded into the distance, Guy realised for the first time that he was ‘alone and afraid’ (1:124), and at this moment, he seems to pause in his recollection and reflect on the momentous event. Interestingly, while doing so, he addresses Mrs Bailey directly, even though she had likely passed away by the time Guy was writing, and would never have read the memoir. Regardless of this he continues, ‘little did you know Mrs Bailey to what hardships you were subjecting two little boys whose only crime was they had lost their father (. . .) you was the one person who was to change the whole course of my life’ (1:124). While Mrs Bailey’s actions inadvertently caused both Guy and Sep much suffering, it is important to note that without her help, life would have taken a very different path, and for this, Guy could do ‘nothing in return except to say a great big thank you’ (1:124).

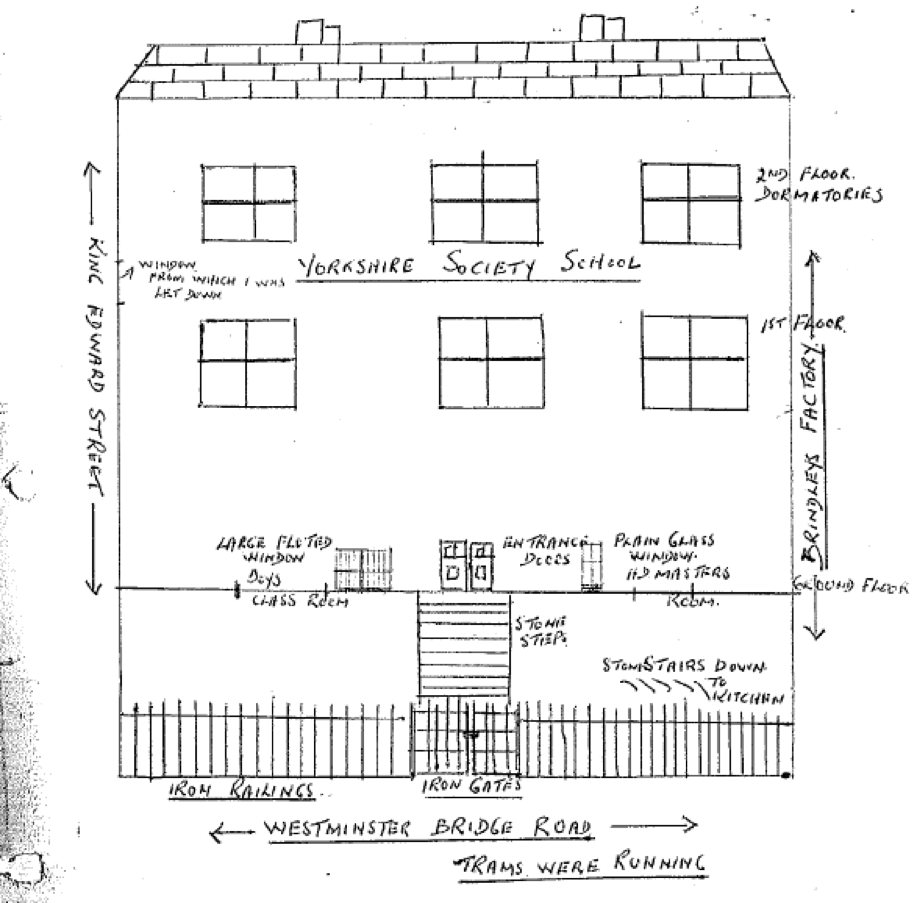

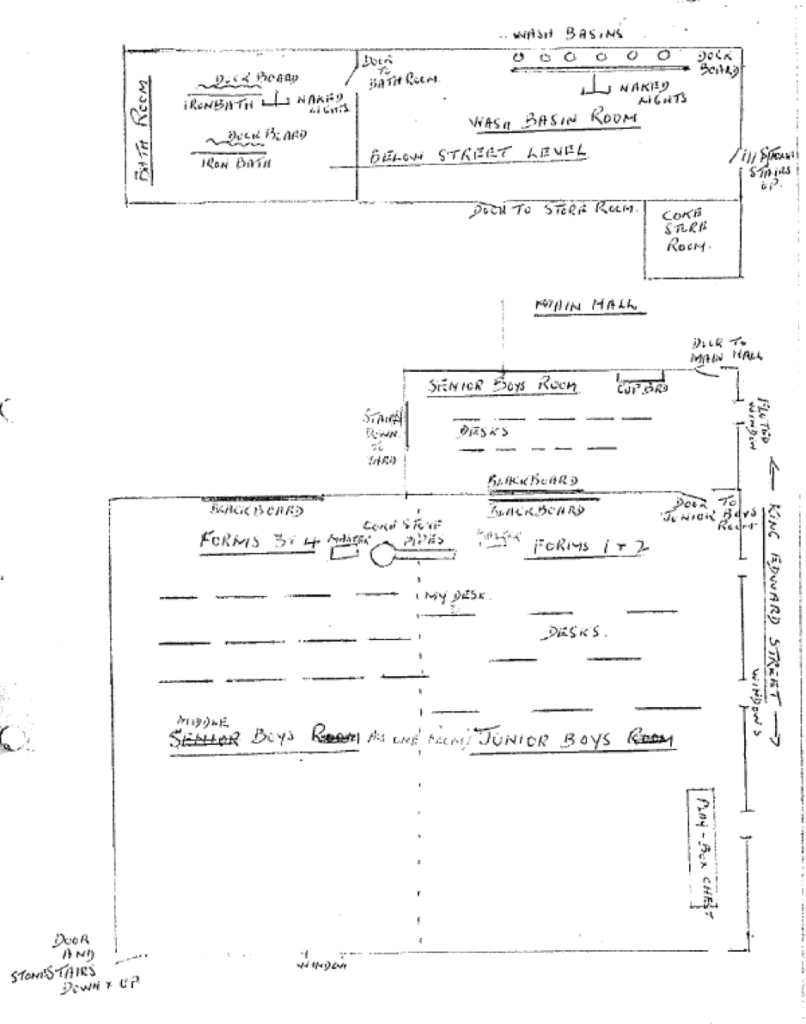

Arrival at School and Staff

After the emotional journey to London, Guy and Sep arrived at the Yorkshire Society School, where the Headmaster and his wife ‘Mr and Mrs Norton’ greeted them (2:15). After the introductions, the ‘new boys, were taken upstairs to [their] dormitory and shown [their] beds’ (2:15), and Guy was pleased to discover that he would remain close to Sep, as his ‘was in a corner under a window next to [his] brother’ (2:15). Following this, the children were shown to their classroom, and their desks, where they would spend ‘a number of hours’ over the next two years, sitting on ‘the hard-wooden seat’ (2:15). Although, Guy reflects that he was surprised by ‘the comfort it gave [him] in the hour of [his] troubles’ (2:15). The classroom was reasonably sized, and arranged so that ‘twenty boys’ could use the space to work in lessons, play and even rest, as sadly ‘there was nowhere else’ (2:15). Once settled and reunited with his luggage, Guy introduces the ‘only staff with whom [the] boys came into contact with’ (2:16), and provides some basic details of their character and physical appearance:

- Mr Norton: 55 years of age, six feet tall and of average build, with grey hair, moustache and pince-nez spectacles. A pleasant manner, but a typical school master (2:16).

- Mr Brown: around 40 years of age, small, clean shaven, quick and alert, always smartly dressed, loud and noisy (2:16).

- Mr Gloster: around 45 years of age, dark hair, a good six foot, average build with a drooping moustache, had a calm manner and spoke softly (2:16). In addition to teaching, he was also ‘a special constable doing night work and at weekends’ (2:44), which showed the teacher in a new light to Guy who insists that he ‘always liked Mr Gloster’ and after seeing the injuries he sustained during a night on patrol, this ‘likeness turned to admiration’ (2:44).

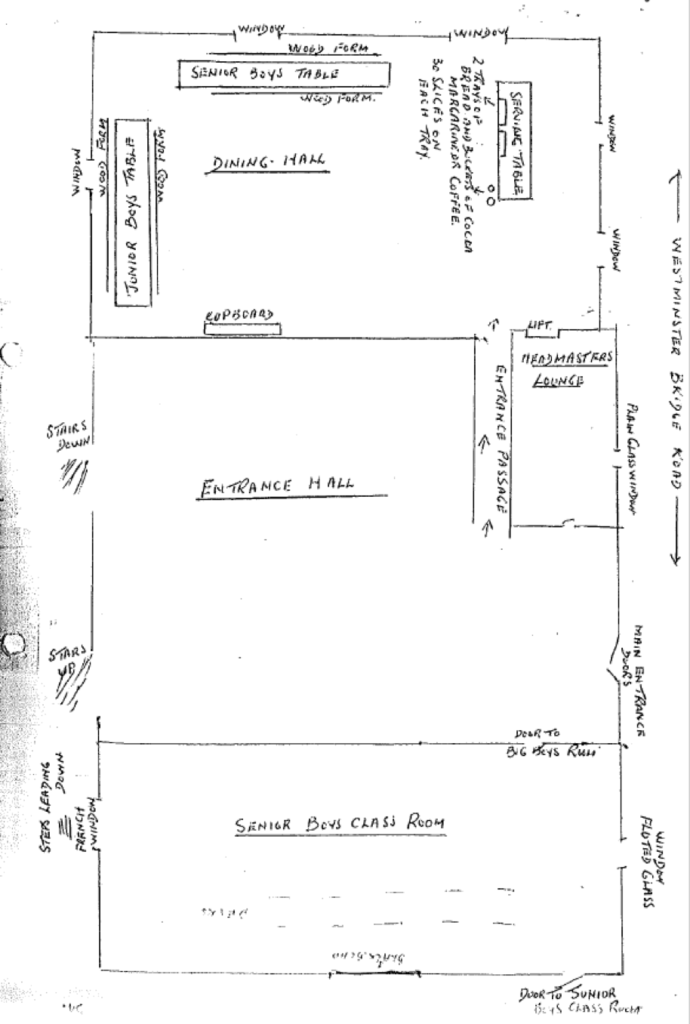

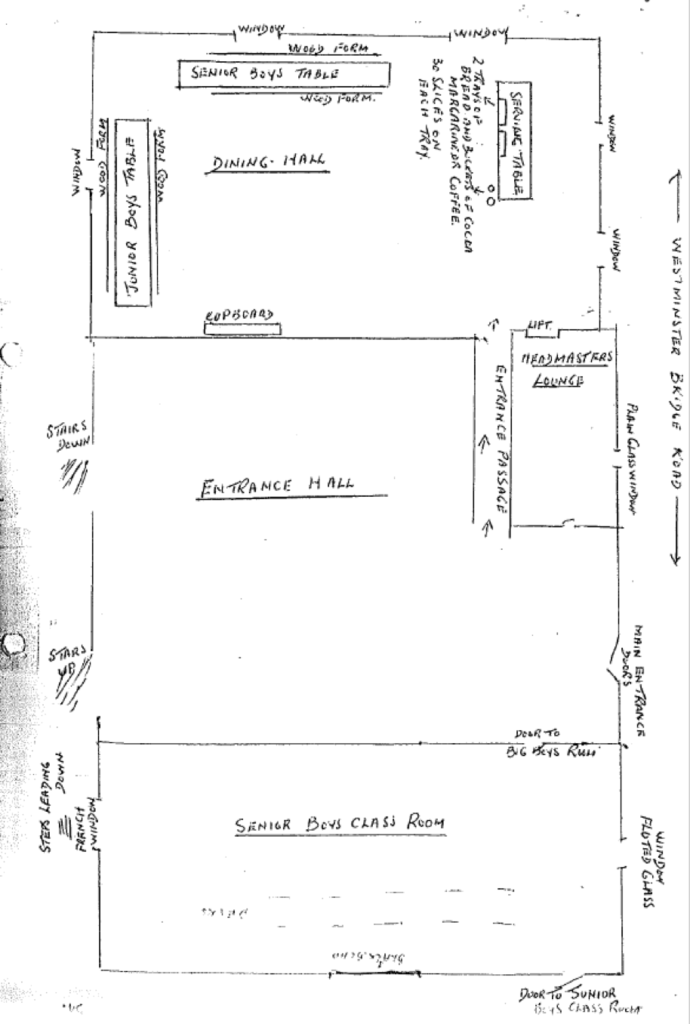

Having met the staff, toured the building, and been allocated his bed, Guy prepared to settle into life at the Yorkshire Society School. As seen below in Guy’s drawings/floorplan (2:14).

Now that we possess a better understanding of why Guy disliked school, and how he came to be in the Yorkshire Society School, we can begin to move forward with the story of Guy’s education. In part two of the ‘Education and Schooling’ blog, we will explore a variety of Guy’s experiences and consider how they may have impacted him throughout his personal and professional life.

If you have enjoyed reading about Guy’s life, you may like to explore the full collection of Guy Oates Posts.

If you would like to read some of our fellow Writing Lives students blogs, then look no further! Here are some of the posts Tasha and I enjoyed for this particular theme:

Keisha Callaghan writes about Amy Gomm, and her education /education-and-schooling/amy-gomm-b-1899-1984-education-and-schooling Amy devotes an entire section of her memoir to talk about her experience of school.

Bronagh Haughey’s blog on Ellen Cooper /education-and-schooling/ellen-cooper-b-1921-2000-education-and-schooling-part-1 provides an interesting read about Ellen’s time at Primary school and Sunday school.

Chris Kalogritsas: /education-and-schooling/allen-hammond-b-1894-education-schooling shows how there was a shift in education which helped many children in the early 1900s through the eyes of the author Allen Hammond Chris has allowed readers to see its benefits.

Bibliography:

Memoir:

Oates, Guy.The Years That Are Gone.Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiographies, University of Brunel Library, Special Collection Library, Vol. 1&2.

Further Reading:

Core:

Gagnier, Regenia. ‘Working-Class Autobiography, Subjectivity, and Gender.’ Victorian Studies 30.3 (1987): 335-363.

Rogers, Helen and Emily Cuming, ‘Revealing Fragments: Close and Distant reading of Working-Class Autobiography’, Family & Community History, 21:3 (2019): 180-201.

Rose, Jonathan, ‘Rereading the English Common Reader: A Preface to a History of Audiences.’ Journal of the History of Ideas. 1 (1992): 47- 70.

Savage, Mike. Social Class in the 21st Century. London: Penguin, 2015.

Vincent, David. ‘Love and Death and the Nineteenth-Century Working Class.’ Social History, 5.2 (1980): 223-247.

Additional:

Burnett, John ed. Destiny Obscure: Autobiographies of Childhood, Education, and Family from the 1820s to the 1920s. London: Alan Lane, 1982.

‘Plate 45’, in Survey of London: Volume 23, Lambeth: South Bank and Vauxhall, ed. Howard Roberts and Walter H Godfrey (London, 1951), p. 45. British History Online

[accessed 8 April 2019].

‘Westminster Bridge Road’, in Survey of London: Volume 23, Lambeth: South Bank and Vauxhall, ed. Howard Roberts and Walter H Godfrey (London, 1951), pp. 69-74. British History Online

[accessed 17 April 2019].

Leave a Reply