Verbena Daphne Brighton (B. 1915): Life writing, class & identity

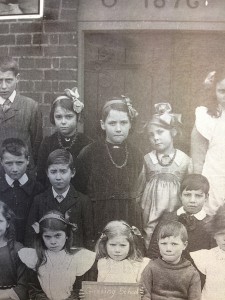

As Brighton explains in her memoir, she has a fascination with dress. In the featured picture of her and two of her sisters it is clear to see that the Brighton sisters are dressed more elaborately than the rest of their school class. Whilst the rest of their class are wearing basic pinafores, they are wearing pretty dresses accessorised with necklaces. This indicates that their family were the more elite of the working- class society as the girls are dressed more expensively. Also, the three sisters are wearing noticeably big, dress bows in their hair which stand out as a key of status. All three daughters look groomed in comparison to the rest of their class.

In the opening chapter of her memoir, Brighton describes her house. Not elaborate, nor poverty stricken her house is pictured as comfortable. Her house is described with character and she explains that the majority of the furniture contained in her house was passed down from a deceased relative. However, in comparison to a regular working- class home it is described as above average. Brighton describes the ‘Best Room’ as having large pictures of family members featured on the walls. This imagery is portrayed as a grand room in her home.

Living in the rural area of Norfolk, Brighton’s family are fortunate to be situated away from the poor quality of working-class city life. She describes that her home is situated amongst plenty of rural land which she describes as ‘beautiful common land’, which is a pleasant atmosphere for children to be brought up in. It could be assumed that Brighton’s family are economically more comfortable for a working- class family.

Brighton reveals that her father, much older than her mother works and owns horses, but it is unknown whether her mother has an occupation. It could be assumed that Brighton’s mother is a housewife who stays at home to look after her children and the home. This would suggest that Brighton’s family are more privileged than the majority of the working- class as she is not doing manual labour in a factory with other women.

It is evident whilst reading her memoir that Brighton was an educated lady. She has accurate grammar and spelling and cleverly uses Norfolk dialect when quoting somebody from her area in her memoir. She frequently mentions reading throughout her memoir and religious singing. Brighton published her own memoir Nuts ‘n May which gives an indication of her educational background.

According to the BBC Great British class calculator Brighton comes under the ‘traditional working class’ category. Brighton’s nostalgic reflection of her childhood is similar to the commemorative narrative form of writing which is defined by Regenia Gagnier for ninteenth century working-class autobiographies in Britain. [1] She reflects on her idyllic childhood in a nostalgic manner. Gagnier states in her work that only a tenth of autobiographies are written by women explaining that they are under represented.[2] This statistic highlights Brighton’s determination to create an autobiography as she published her own memoir.

Typical of female autobiographical writing is confessional narrative, Brighton’s memoir does not follow this narrative form of writing. This could be because her memoir is filled with innocence as it is an account of her childhood.

Although I would believe that class is part of Verbena Brighton’s identity, it is difficult to confirm whether she is defined by class as her memoir is a reflection of her childhood memories. Therefore, Brighton’s political views nor her families are mentioned in her memoir due to her focus being on her idyllic memories of her background in Norfolk.

[1] Gagnier, Regenia. ‘Social Atoms: Working-Class Autobiography, Subjectivity and Gender.’Victorian Studies 30.3 (Spring 1987): 335-363

[2] Gagnier, Regenia. ‘Social Atoms: Working-Class Autobiography, Subjectivity and Gender.’Victorian Studies 30.3 (Spring 1987): 335-363

Leave a Reply